Fred Haise talks about going to the moon and back (barely)

|

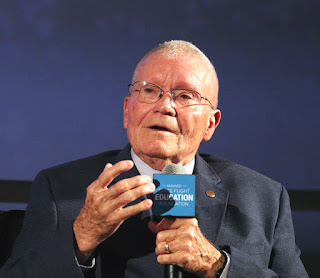

| Apollo 13 astronaut Fred Haise talks about his experience aboard the ill-fated flight to the moon during a Thought Leader Series lecture March 13 at Space Center Houston. (Photo by Joe Southern) |

There was a time 48 years

ago when Fred Haise was one of the most famous men off the planet.

His name and face graced

the front page of nearly every newspaper and news magazine in the world. People

were glued to their televisions and radios just to keep up with what he was

doing. Millions of people were praying for him and his crewmates.

Today, few know his name

and he doesn’t have a prayer of being recognized unless he’s announced at an

event. He was the keynote speaker March 13 at just such an event at Space

Center Houston. A full house turned out to hear Haise speak about his days on

the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission as part of the space center’s Thought Leader

Series.

The Apollo 13 mission

launched on April 11, 1970, and was to be the third moon-landing mission. A

mishap on the way crippled the spacecraft and endangered the lives of Haise,

Jim Lovell and John “Jack” Swigert as they hurled toward a moon they would no

longer be able to set foot on. Their “routine” mission became an epic struggle

for survival that captivated the world. In 1995, a movie about the mission

directed by Ron Howard and starring Tom Hanks became a smash hit and painted

with broad strokes a picture of what the adventure was like.

Haise, now 84, was able

to color in many of the details during his talk at Space Center Houston. The

event was hosted by Daniel Newmyer, vice president of education at Space Center

Houston, who presented questions to Haise during the hour-long talk.

Haise was born in Biloxi,

Miss., in 1933, and early in life wanted to be a sports reporter. He was the

sports editor of his high school newspaper and did the same in junior college

before his education was interrupted by the Korean War.

“I joined up to fly

airplanes when I had never been in an airplane in my life,” he said.

He punted his sports

writing career once his love of flying got off the ground. Haise, like many of

his NASA colleagues, came to the space agency from a military background. He

was selected as an astronaut in 1966 as part of the fifth astronaut group.

His first assignment with

NASA was on the back-up crew for Apollo 8 – the first mission to take humans

around the moon. One of those humans was his future commander, Jim Lovell.

Haise was assigned to the back-up crew when Michael Collins became ill. He

joined Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as back-ups and would have advanced with

them to Apollo 11, but, “Unfortunately as it turned out, Mike Collins got

well.”

His second assignment was

on the back-up crew for Apollo 11, where he served as Aldrin’s back-up as the

lunar module pilot.

“So I ended up serving

another back-up assignment as Buzz Aldrin’s back-up on the Apollo 11 crew with

Jim Lovell and Ken Mattingly at the time,” he said.

As the rotations went,

back-up crews became prime crews three flights later. That would have put them

on Apollo 14, but they were bumped up a flight to allow Alan Shepard more time

to train after having had surgery to correct an inner ear problem.

Lovell, Haise, and

Mattingly trained for the mission, but Mattingly was grounded after being

exposed to the measles.

“Jack joined our crew two

and a half days before launch,” Haise recalled.

His ability to do that

was a testament to NASA’s training protocols.

“It proved out the

methodology at that time that the prime and back-up crews did pretty much the

same thing,” he said.

Haise said they were all

confident in Swigert’s ability.

“We had done the

preparation … we knew our business, we were confident that we could handle

anything short of catastrophic,” he said.

About three-fourths of

the way to the moon, the crew had just finished filming a television program

and were stowing gear when flight controllers called Swigert and asked him to

stir the oxygen tanks. He did and an electrical short caused the second tank to

rupture.

“They call it an

explosion. It was not an explosion, fortunately,” Haise said. “The oxygen tank

had a short and an over-pressurization and somewhere a seam burst. It built up

pressure in that compartment and that blew off a quarter panel of the spacecraft.

If it had been an explosion there would have been shrapnel and I wouldn’t be

here today because behind the very thin wall where those tanks were, is where

the propellant tanks were. So fortunately we didn’t have a tank explode.”

The shockwaves from the

rupture flipped several switches, closing off valves and shutting down two of

the power cells. They couldn’t be re-started.

“There wasn’t any Plan B

waiting around to handle all of the things that needed to be handled,” he said.

Although the astronauts’

lives were endangered, the true heroes of Apollo 13 were the hundreds of men

and women working on the ground in mission control to bring the crew back

safely. The crew acknowledged that by placing a mirror from their flight on the

wall of historic mission control.

“Mirror was for looking

at things you couldn’t see,” Haise explained. “We wanted that to be in honor of

the people at mission control – many I talked to after the fight, I figured

they got less sleep on the ground than I got in flight – it was an incredible

effort for some people. Some people told me they didn’t go home, they just lay

down on the floor in the hallway … It was obviously an appreciation of that

effort that was made during our flight to get us home.”

A plaque under the mirror

reads: “This mirror, flown on Aquarius, LM 7, to the moon April 11-17, 1970,

returned by a grateful Apollo 13 crew to reflect the image of the people in

mission control who got us back. James Lovell, John Swigert, and Fred Haise.”

“I hate to admit it, but

grateful is spelled wrong,” Haise confessed.

Although Apollo 13 went

down in history as a successful failure, there were no Apollo missions without

their glitches.

“There were problems on

every flight. In fact two other flights we almost aborted on, Apollo 14 and

16,” Haise said.

After the moon landing

ended, Haise looked into the data from each flight.

“Apollo 13 had the second

to least number of anomalies. It had a big one,” he said to great laughter.

“Apollo 17 had the least of all of the missions.”

After Apollo, Haise

helped develop the space shuttle and flew the first test flights of the

Enterprise off the back of the 747 that now sits in front of the Space Center

Houston with a replica space shuttle on its back. He and Gordon Fullerton made

three test flights with Enterprise. In 1978, Haise retired from NASA and took a

job with Grumman Aerospace Corporation.

Today he lives in

Mississippi and works with the nonprofit Infinity Science Center, a counterpart

to Space Center Houston.

As for the movie, Haise

praises the job they did, though he is quick to make note of inaccuracies and

exaggerations.

“Ron Howard told me NASA

gave him all the air-to-ground transmissions and he listened to all of that. ‘It

sounded to me like you never had a problem. We had to put some of that stuff in

there to humanize you,’” he said.

A question all the Apollo-era astronauts get is how they

feel about humans going back to the moon.

“NASA right now, I wish we were further along in doing

things farther out – exploration if you will – back to the moon because we

really did a very cursory look at that feature with six landings,” he said. “We

had six landings at very select spots that geologists chose based on what they

thought the geologic returns would be and tell them more about the cosmology of

the moon. There’s a lot more there to have looked at and surveyed, and of

course another favorite topic has been about going to Mars, which has for a

long time been talked about. I had hoped we’d have the similar type of support

we had during the Apollo era. The right things aligned to make sure the

president, Congress, the general public, was in favor of the mission that would

allow it to be financed.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home